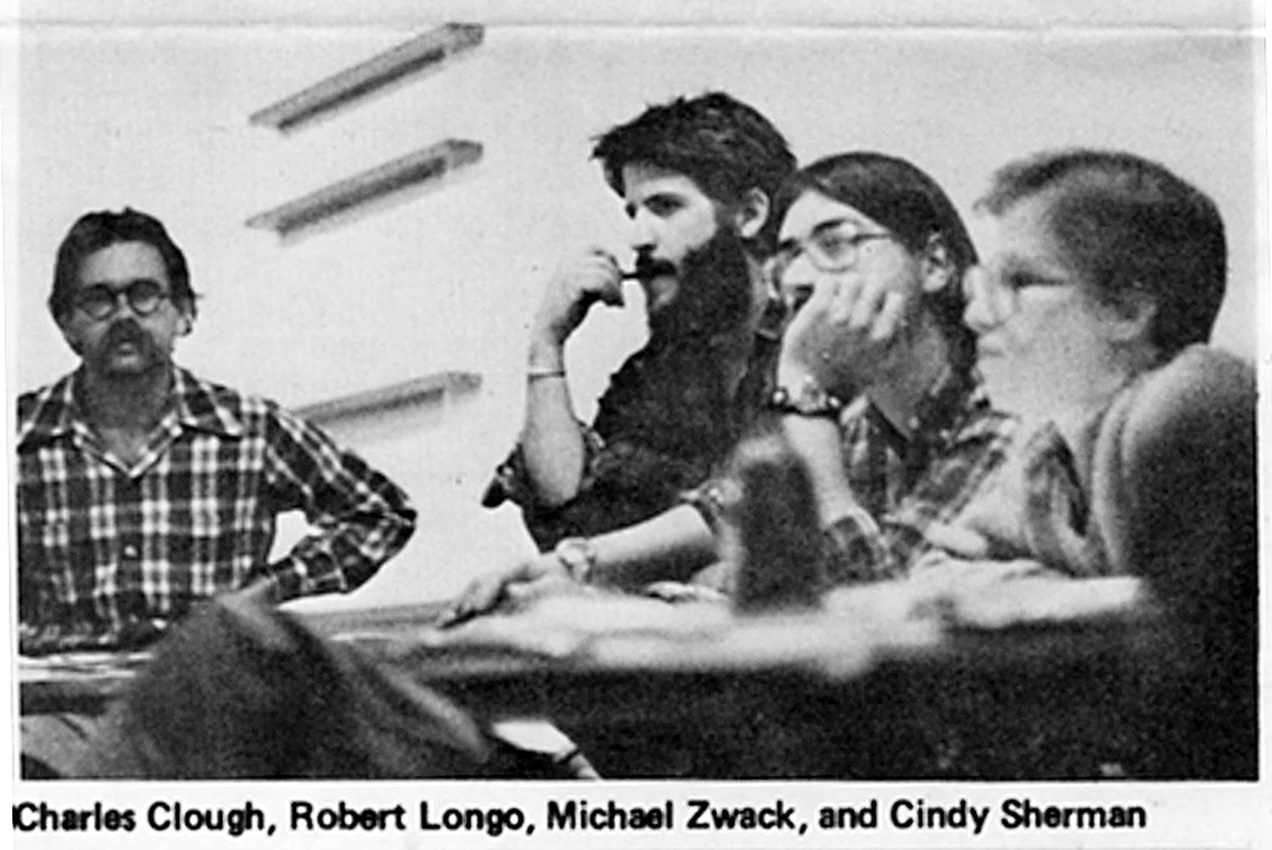

In effect, Hallwalls was Clough’s instrument for self-education. His research by visiting exhibitions and reading corresponding reviews and theoretical essays led to meeting artists in their studios to curate exhibitions and arranging their visits and presentations. This knowledge focused Clough’s attention on the unfolding of contemporary art in relation to the aesthetic that he was forming for making his own work. Clough and Longo divided curatorial attention into painting and photography for Clough and sculpture and time-based media for Longo.

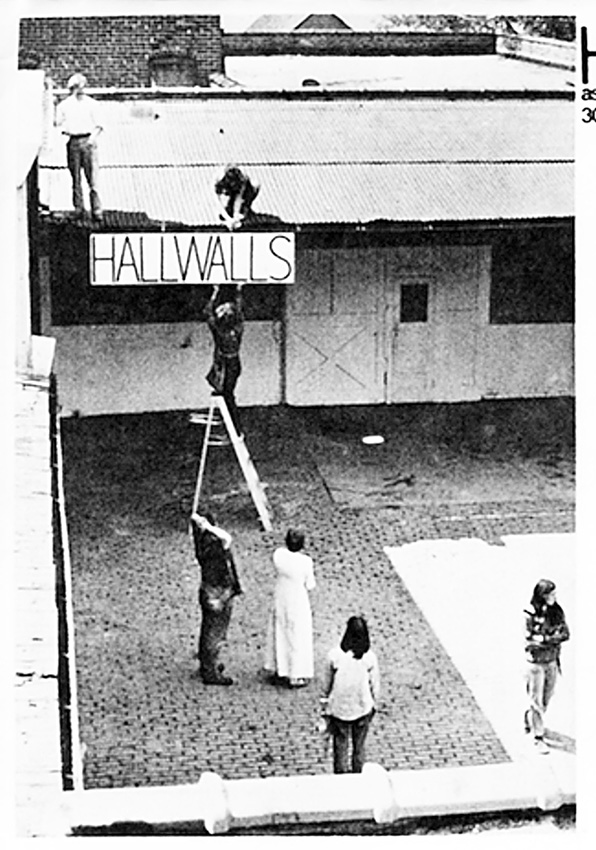

Hallwalls operation was enabled by its proximity to and relationships with the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Artpark in Lewiston, New York, the art departments at SUNY Buffalo and Buffalo State College, and Media Studies at SUNY Buffalo insofar as these organizations made western New York attractive to ambitious artists.

Historically the art of the 1960s included Post-painterly Abstraction, and Pop. While Clough considered figures such as Warhol and Rauschenberg too famous to pester, artists of Minimalism, Conceptualism with attendant Earth art, Body art, and documentary photography, and Structuralist Cinema, proved willing to share in the context of a younger artists’ audience. There also existed art being shown by Paula Cooper Gallery and Holly Solomon Gallery of an idiosyncratic nature that defied classification. Curating was Clough’s method of learning contemporary art. For example his three-part “Approaching Painting” (1976) show included works by, Part 1: Jennifer Bartlett, Bruce Boice, Sol LeWitt, Robert Mangold, Richard Tuttle, Part 2: Joel Fisher, Marcia Hafif, Frank Owen, Robert Petersen, Robert Ryman, Richard Serra, Michelle Stuart, Part 3: Lynda Benglis, Ron Gorchov, Bill Jensen, Marilyn Lenkowsky, Elizabeth Murray, Judy Pfaff, Jane Rosen, Barbara Schwartz and John Torreano. His “Artists Use Photography” (1976-77) exhibition included work by: Mac Adams, John Baldesarri, Jared Bark, Bill Beckley, James Collins, Robert Cumming, Jan Dibbets, Susan Eder, Carole Gallagher, Jack Goldstein, Douglas Huebler, Bruce Nauman, Liliana Porter, Marcia Resnick, Eve Sonneman, and Ger Van Elk.

By the spring of 1977 as Clough was beginning the process of not-for-profit incorporation of Hallwalls, Longo left Buffalo for New York City in pursuit of his art career. After establishing Hallwalls’s independence from the Ashford Hollow Foundation, Clough also left for New York in 1978.

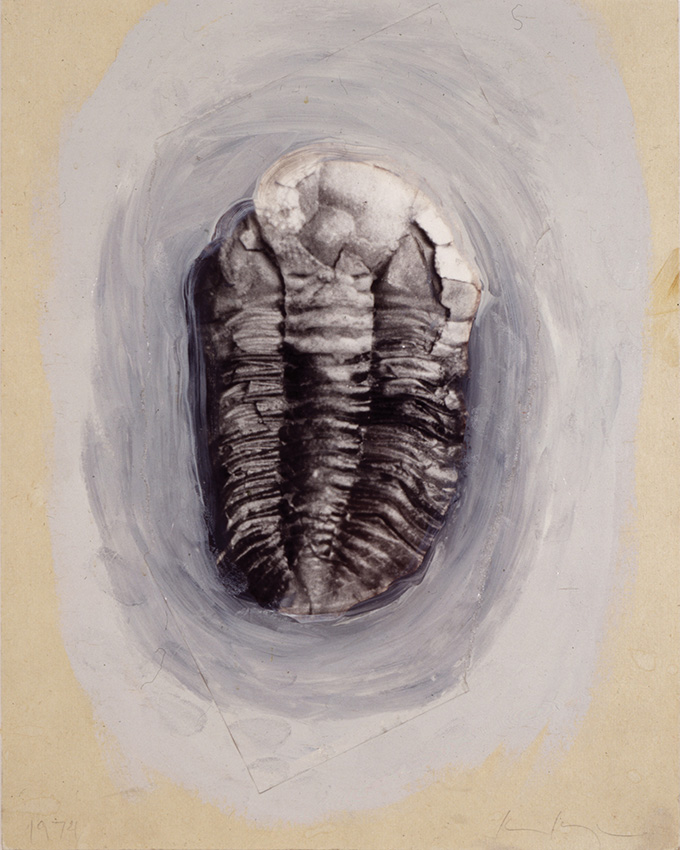

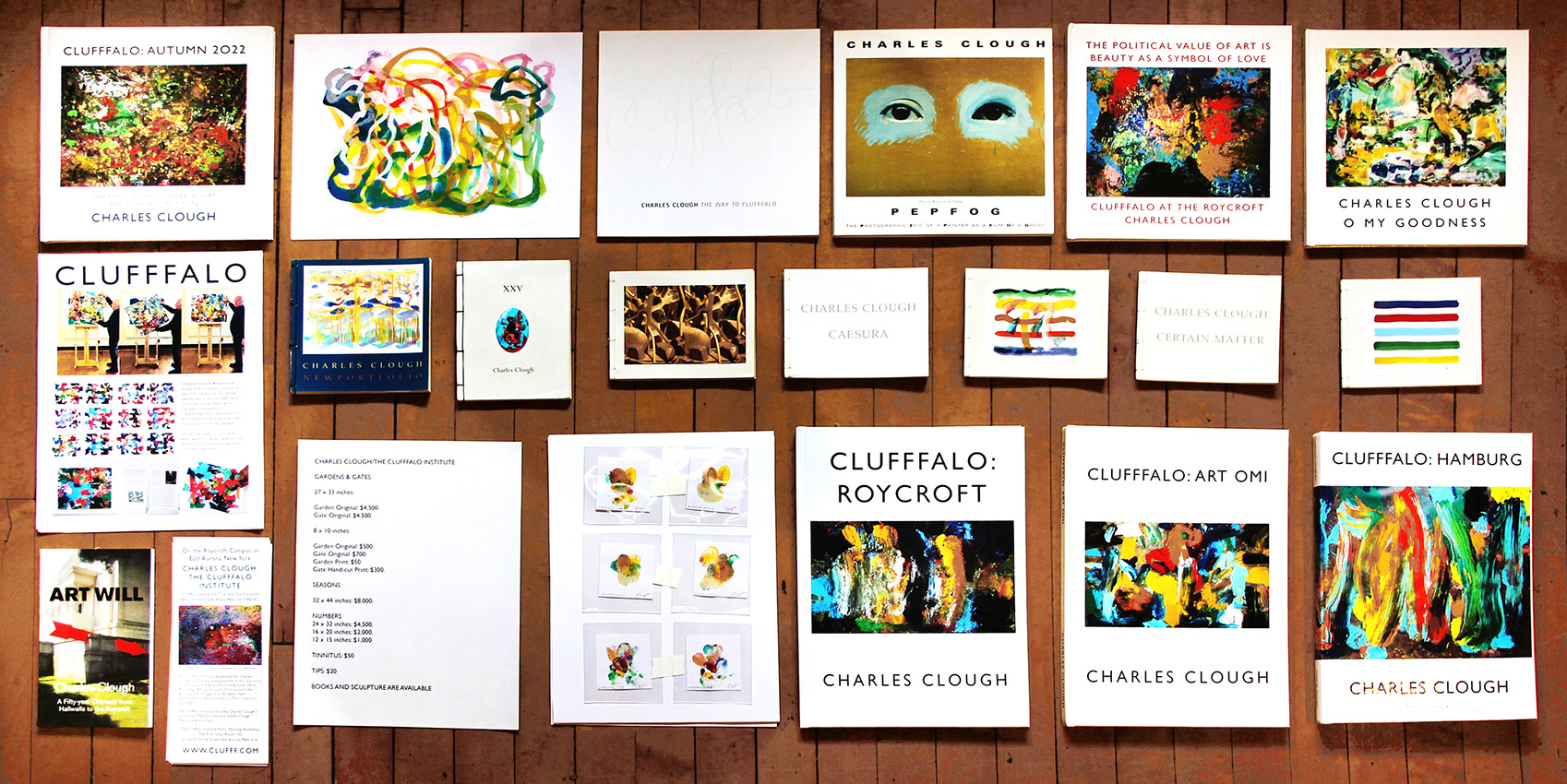

Through Clough’s reading, curating, journaling and experimenting with paint and photography, he determined in 1976 that his “job description” would be, to make “the photographic epic of a painter as a film or a ghost,” or “Pepfog.” Through his intensive study of Marcel Duchamp’s work, he came to understand the entirety of an artist’s work as being crucial to the artist’s meaning, and that discrete paintings or photographs constituted a “frame” within the “cinema” which is the artist’s oeuvre. While Clough has been embraced by the art world as a painter, an underlying basis of photography and structure of cinema constitutes the completeness of his work.

Clough’s first solo exhibition was presented in SUNY at Buffalo’s student union in 1973 and his first New York City exhibition was at Artists Space in 1976 with Hallwalls artists, Longo, Cindy Sherman, Diane Bertolo, Nancy Dwyer and Michael Zwack.

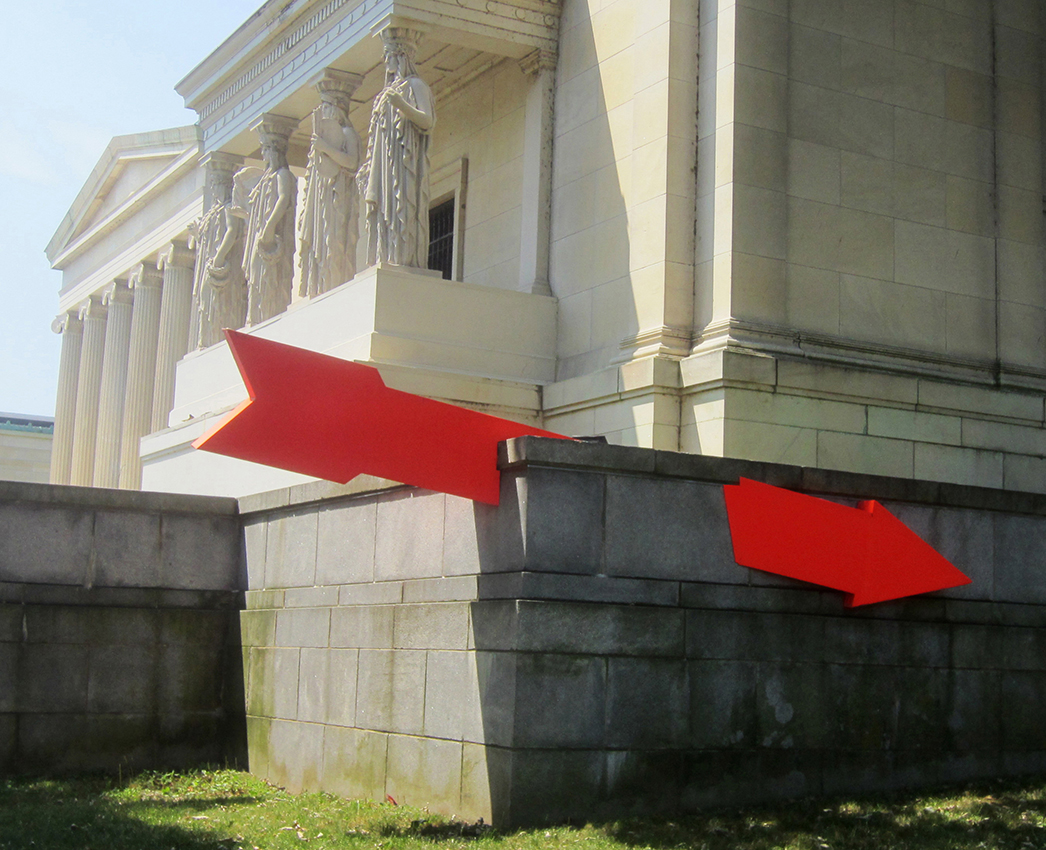

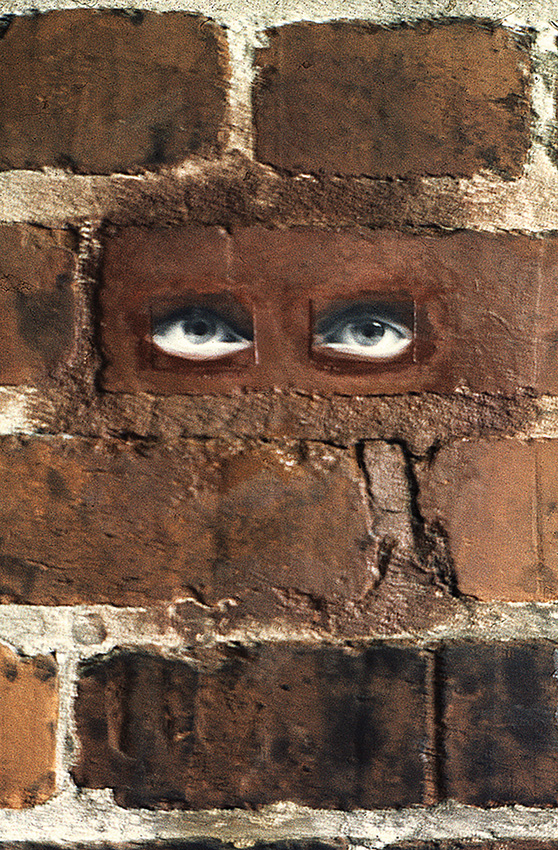

Beginning with photos of his eyes “painted into walls,” Clough’s works evolved as cutout collages to enamel on canvas works painted with pads on the ends of sticks, known as “big fingers.” Curators and critics responded to Clough’s work in the 1980s and ‘90s:

Dr. Anthony Bannon wrote in the catalog for “The Painterly Photograph,” in 1980: “Charles Clough’s art is an art of renewal, an extension of replica objects into possibilities for still new replication. One’s assumptions of how things ought to be, such as predictable, tidy and categorical, are put asunder. Although the size, whimsy, color and youthful dare-doing of the work has its decorative pleasures, Clough’s work is not meant for casual attention. Conceptually, an everlasting quality of his effort is found in its consequences: that Clough goes a long way in the liberation of photography and painting from their cubbyholes. While creating a generation of commercial materials, Clough also makes homage to the very history of art from which he emerges. The range of his work, its incorporation of diverse image objects, structures and references, suggests a love affair with the whole of life and those things which life makes—its culture, whether mundane or lofty.”