I established my art studio in East Aurora, New York in 1971. I moved it to Buffalo, New York, various locations in New York City, Westerly, Rhode Island and back to East Aurora while maintaining residence in New York City.

As of July, 2015 the Clufffalo Institute is located on the Roycroft Campus in Suite 120, The Print Shop, 21 South Grove Street, East Aurora, New York 14052.

I have presented my art in more than 80 solo exhibitions, 150 group exhibitions and more than 600 of my works are included in the collections of more than 70 museums.

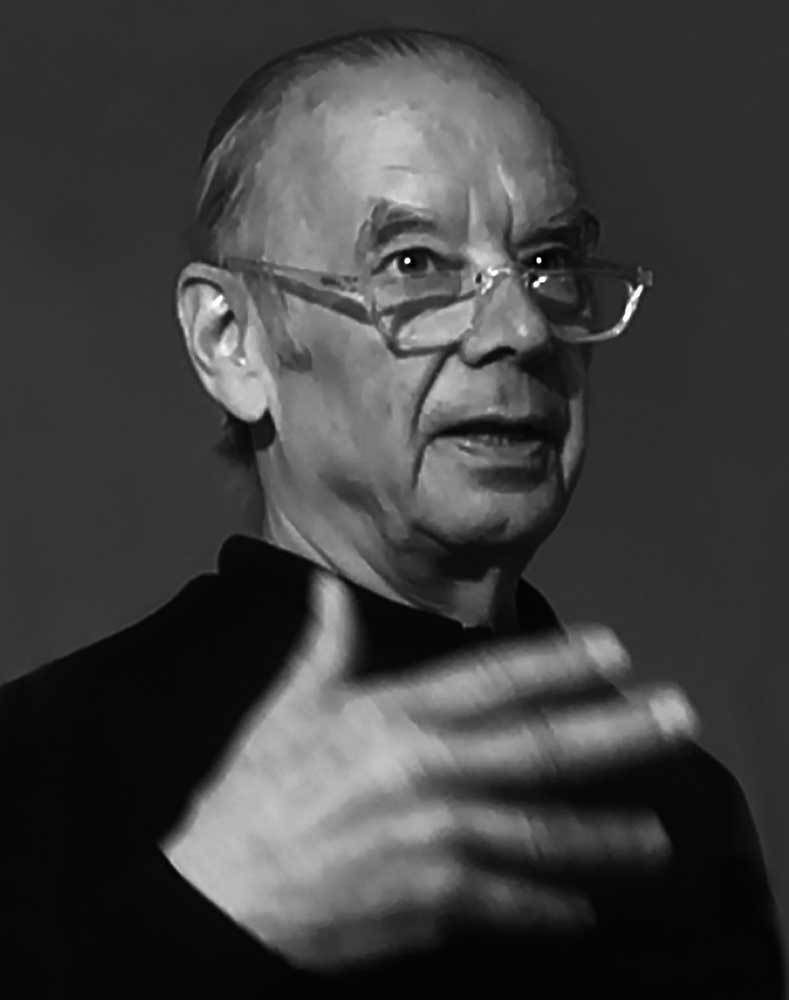

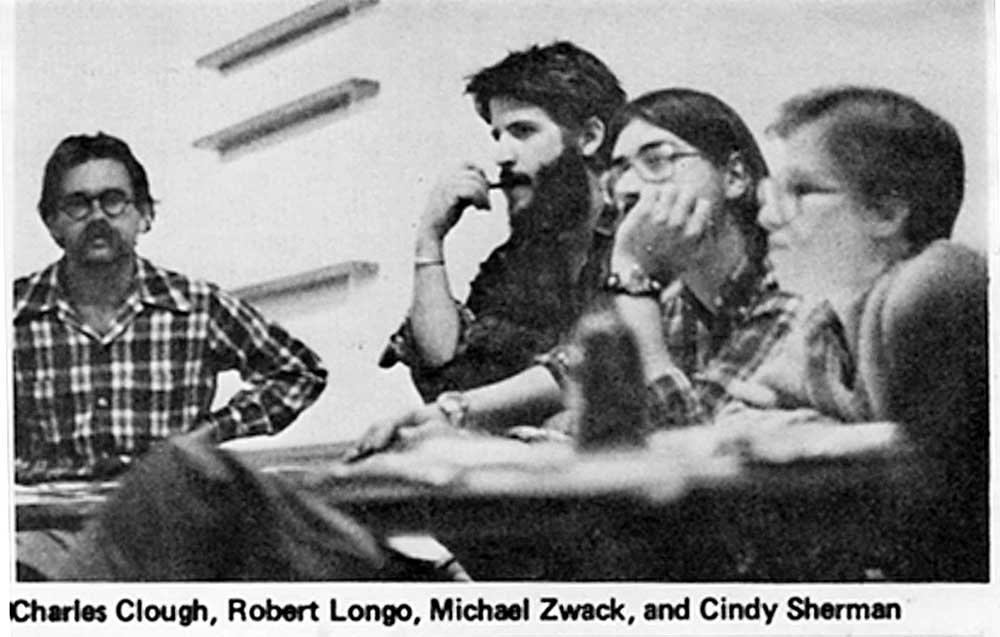

Clough first came to my attention as part of the great return to painting that marked the dawn of the 1980s. He was one of the Postmodernist abstract painters associated, in my mind, with the school of Collins & Milazzo in New York, and was also associated with the group of artists (Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo) who emerged from the Hallwalls art scene in Buffalo, N.Y. He showed his work downtown, in SoHo and the East Village, and lived in a small apartment in Little Italy with his wife and two small sons.

Back then, I might have said that Clough was a Neo-Geo artist, but in a completely contrary way, since his work is not in the least bit “geo.” Rather, his paintings are explosively formless, like a volcanic eruption or a storm during sunrise. Clough’s paintings are extravagantly colorful, suggestive of nature at its most dramatic, whether roaring tempest or expansive pastoral. His canvases make an almost magical abstract claim to the kind of epic quality that is so familiar from classical art, ranging from the celestial spectacles of Giambattista Tiepolo to the New World vistas of the Hudson River School, and perhaps including, more recently, the paintings of Anselm Kiefer.

At the same time that Clough reaches for the heavens, so to speak, he is utterly grounded in the materialist imperatives of contemporary abstract painting. That is to say, his paintings immediately declare themselves unequivocally as paint on canvas, as a “flat surface covered with colors” as Maurice Denis had it. In fact, as if to underline his paintings’ materiality, Clough’s pigment is, if memory serves, commercial sign-painter’s enamel, specifically designed to withstand extremes of weather. Arguably the most material of paints, sign-painter’s enamel is notable for its durability, sheen and high lead content. Like Robert Ryman, Clough restricts himself to his art’s most elemental qualities. But where Ryman opted for the purity and simplicity of white, Clough embraces the glories of the entire color spectrum. With his complete palette, he makes the paintings that Ryman just couldn’t make (apologies to Martin Kippenberger and his “Paintings Pablo Couldn’t Paint Anymore”). Ryman plies a brush, needless to say; it determines the very essence of his art. Clough uses a different tool, one of his own devising, a fact that is similarly central to his work, both defining it and making it possible (my apologies for taking so long to get to this important point). What is this tool? Clough makes his paintings with a custom-designed, upholstered drumstick-like wand that he calls his “big thumb.” A silly name to be connected to serious enterprise — abstract painting — but the notion of the “thumb,” of the unique originality of the thumbprint, of being “all thumbs,” amplified still further in Robert Hughes’ assault on the then-young Julian Schnabel and his “five fat thumbs,” is not without avant-garde resonance. Clough’s “big thumb” is a tool like no other, a tool whose utility, counterintuitively, lies in its undifferentiated clumsiness. It makes only blots and smears.

Clough’s “big thumb,” then, embraces the kind of gaucherie that has characterized advanced art since the dawn of modernism; the term was used, for instance, by late-19th-century critics to describe Paul Cezanne’s unconventional painting style. Clough wields this tool (or it could be said that the tool wields him) to make painterly marks that magically metamorphose like an intricate Rorschach Blot into an astounding array of abstract landscapes, cosmologies, ascensions, nativities and all manner of other compositions. Each metamorphosis is obviously subjective and almost mechanical, but nevertheless uncanny, wonderful and and sublime.

More recently Clough has moved what was a solitary studio practice out into the public arena, expanding his art-making into a communal enterprise. It’s an admirable project, and one that I support. If I were king of the world, though, I would grant Clough the resources to produce a series of large, new paintings, works that would strive to capture the epic dimensions of contemporary life.